I recently came across a free webinar in Psychology Today by Janina Fisher on “Overcoming Trauma-Related Shame and Self-Loathing.” Her argument led me to consider how Lacan’s theory of psychoanalysis offers a valuable and much needed contribution to the current discourse around the problem of psyche and body. People today are often very hesitant to apply French theory to actual practice outside the cultural field. However, I believe psychosomatics must be considered through the lens of the science of psychoanalysis, though it has been wrestled from its hands.

In her hour long video, Fisher discusses the potentially beneficial function of shame, which may serve as a signal notifying us of interpersonal dangers that could result from our actions and so help us to correct our behavior. Fisher is not alone; even psychoanalysts talk about “normal” shame which, unlike its pathological counterpart, is credited with an important adaptive function. Lacan, however, suggested that shame might be one feeling worth getting rid of altogether:

“In the mean time, to die of shame is the only affect of death that deserves -deserves what? -that deserves to die.” – Lacan The Other Side of Psychoanalysis 1969

Lacan asks a question: can shame kill? For him, shame is directly related to the death drive, which is a tendency to desire symbolic stability, even at the cost of one’s life. This is the foundation of somatization in general: preferring to feel physical discomfort and pain rather than actually experience tabooed psychic content. Shame often points at a raw, Real reality and unconscious content that interferes with an individual’s imaginary conception of their world. It is not an innocent adaptive function, but a repetitive attempt to integrate the difficult Reality of the experience into coherent structure that does not too deeply disturb the patient’s symbolic universe. Psychosomatic problems are symptoms of the failure of this process.

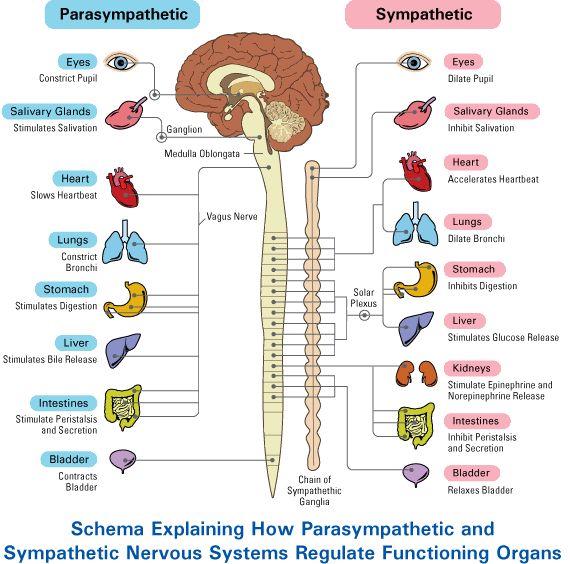

What I find really striking and problematic in Ms. Fisher’s approach was how she manipulates physiological terminology on the concepts of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems to prove her point. She claims that the sympathetic system is related to high excitation, and the parasympathetic system to low excitation. She then claims that because shame is related to feelings of submission and depression, it should activate the parasympathetic system, and thus prevent maladaptive behavior and acting out. However, even mainstream research shows that though depression might be debilitating, but it is not relaxing like the parasympathetic nervous system, as Ms. Fisher claims. And according to the 1994 study published by the researchers from Veteran Affair’s Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center, depression actually activates the sympathetic, not parasympathetic nervous system.

I completely agree that depression is related to shame. Lacan speaks of depression as a moral failure during his television appearance in early 70s:

“[depression] is simply a moral failing, a moral cowardice, which is, ultimately, only situated by thought, that is, by the duty to speak well or to find oneself again in the unconscious, in structure.”

Controversial as this may sound, I believe that it is essential to acknowledge the extent to which the need for belonging, which always involves locating oneself as a part of the symbolic structure, is a key element to consider in discussions around both shame and depression. What shame responds to and renders unbearable is one’s uncertainty, feelings of rejection and exclusion, and incomplete sense of self.

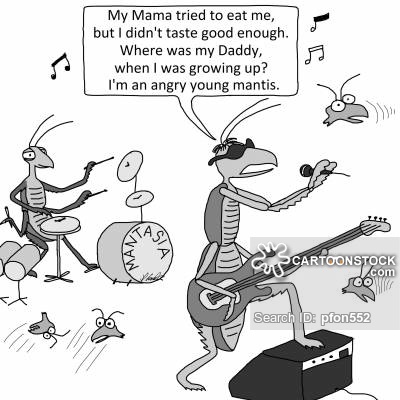

Simply speaking, shame and moral failure are terrifying, and produce a fight-or-flight response, even if it is internalized into psychosomatic manifestations. Lacan points out that shame originates in early childhood, when a parent, as the big Other, maps the child’s place in the world through language-based communication. Children internalize this image of the law-forming Other as a monstrous omnipotent figure which Lacan even compares to a giant praying mantis that might or might not rip off your head. This image of an unpredictable and strong parent fantasized to be punishing one for a real or imagined transgression that produced shame is exactly the projected gaze of the monster from which one is physically readies to fight or flee from. That is why both shame and depression elicit sympathetic, figh-or-flight reaction. A fixation of early childhood anxiety which reappears in social interactions throughout one’s adult life, it is this traumatizing gaze that constitutes the indiscernible kernel that such irrational somatization is attempting to defend against to preserve the integrity of the ego. I will expand on relation of ego and psychosomatics in the future posts.

However, there is nobody really behind you and this fantasy of punishment is most likely far removed from the actual consequences of your actions. Nonetheless, even without actual or self-inflicted (in case of perversion) physical punishment, constant activation of the sympathetic nervous system does have consequences to longevity, as the other name for it is stress.

Being ashamed is stressful, but that tells us little about the mechanism of its psychic function. Parasympathetic nervous system activation, also known as relaxation, might be an ideal, but claiming that it can be fostered by submitting to healthy shame is just physiologically false. Shame is an experience of a malfunction in the symbolic matrix which is always accompanied by the fight-or-flight reaction of sorts. Perhaps in the case of post-traumatic stress disorder this failure is amplified by the traumatic experience, but it may be causing even more covert harm in the bodies of people with no signs of disability.

The way out is not through the dissection of the body, but by facing the looming symbolic monstrosity, the gaze everybody is so eager to escape, but whose presence is even more ever-present in the disintegrating society of our times.

Today. A woman, speaking in Russian, told me she has abdominal pains, and asked if I am a therapist. I told her that yes, I am a psychotherapist. She was not satisfied: “But are you a doctor therapist?” (Врач Терапевт in Russian). I explained to her that I am not a medical doctor, but that I do work with psychosomatic and stress related issues. She apologized, and quickly hung up.

Today. A woman, speaking in Russian, told me she has abdominal pains, and asked if I am a therapist. I told her that yes, I am a psychotherapist. She was not satisfied: “But are you a doctor therapist?” (Врач Терапевт in Russian). I explained to her that I am not a medical doctor, but that I do work with psychosomatic and stress related issues. She apologized, and quickly hung up.